ON THIS DATE (10TH AUGUST) 98 YEARS AGO - IRA EXECUTIVE REVIEW PAST ACTIONS AND MAKE FUTURE PLANS.

On August 10th (and 11th) 1924 - 98 years ago on this date - the remaining original members of the pre-Civil War Irish Republican Army Executive (that is those of them who had opposed and fought against the Treaty of Surrender in 1921), together with the co-opted members of the Executive during the Civil War (about 26 people in all), met secretly to review the past and decide policy for the future.

Ernie O'Malley was voted on the 'Sub-Commission Committee to the Executive for Emergency Consultative Purposes', and it was he who proposed the following motion, at this first post-Civil War general meeting of the Executive :

'That Volunteers be instructed not to recognise Free State and Six County Courts when charged with any authorised acts committed during the War or for any political acts committed since, nor can they employ legal defence except charged with an act liable to the death penalty.'

This motion was passed unanimously, and that refusal to recognise those courts in one way or another lasted until the 1970's.

On the 26th May, 1897, Ernie O'Malley, fighter and author (Earnán Ó Maille, pictured, in 1921, in Dublin Castle, during his 'arrest' - he was using the alias 'Bernard Stuart'), was born in Castlebar, in County Mayo.

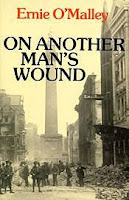

And what an author he was ; his book 'On Another Man's Wound' records the war against the British forces from 1916 until the calling of the 'Truce' in July 1921 and is told by one who volunteered for Oglaigh na hEireann in 1917 and by 1921 was Officer Commanding of the 2nd Southern Division and, later, Assistant Chief of Staff in the Civil War. It is an exciting read, always enthralling, beautifully written, and far and away the best of the Tan War books.

An important theme of his books is the treatment of republican prisoners, who were even then denied prisoner-of-war status : a concern for all IRA prisoners, unaccepted as political prisoners or prisoners-of-war. For all of his republican life, Ernie O'Malley supported their lonely cause - he himself had taken part in the mass hunger-strike of October/November 1923, although medically exempted and suffering intense pain from old wounds and bed sores, for the length of its 41 days, and he was one of the four in Kilmainham Jail, in Dublin, who had wanted to continue.

While in exile in America, his diaries showed support for the republican prisoners in the Free State, of whom he wrote -

"...who are there for the very same reason that the men we read of and revere were imprisoned." Back in Ireland, at a meeting in 1939 of the 'Irish Academy of Letters', he voted in favour of Peadar O' Donnell's motion that a concert be organised to support dependants of IRA prisoners - not surprisingly the motion was rejected.

His was the drama and sacrifice of a really doctrinaire republican - a very brave man, at once ruthless and sensitive, whose contrasting traits of character are well revealed in his autobiographical writings. He was very nearly killed in November 1922 when Free State troops besieged his headquarters, ensuring ill health that affected him for the rest of his life and very likely resulted in his comparatively early death, aged 57.

But while not shirking the possibility of death in action, he fought for military victory, and believed that it was possible. An old Ulster proverb says it is easy to sleep on another man's wound : there are many in Ireland today who rest cruelly or carelessly on the hardships and sufferings of brave men and women who fought and still fight for their country's freedom. The only books Ernie O'Malley wrote were about the Irish wars and it is in those that he should be most remembered.

Ernie O'Malley was brave and energetic in his total dedication to the Republic as proclaimed in Easter Week 1916 : his personal adventures, dramatic and varied, are an integral part of the wider significances of the national struggle. Unlike some of his companions who later called themselves 'the Old IRA' or 'the Neutral IRA', he did not change his republican beliefs - indeed, he recognised that some Irish have always helped in the conquest (those people and groups are what we on this blog refer to as 'service providers' ; they can be found everywhere, in all walks of life, and cohabit with each other in the posh halls and corridors of Leinster House and Stormont, to name but two such venues).

During the 'National Emergency' years of World War Two, de Valera himself was very keen to have so famous a fighter as Ernie O'Malley join the Free State army and pressure was put on him to follow many renowned republicans into its ranks (the oft-mentioned 'republican-gamekeepers-turned-Free State-poachers'). O'Malley asked - "Would I have to inform on my former comrades and work against them? But of course! Join? Certainly not!" And that was that. Indeed, only a month or so before his last illness he was writing in his diary - "I can never see a peeler without feeling uneasy.."

Hopefully, Ernie O'Malley's books should fire the imagination of a new generation of Irish republicans. In so many ways 'On Another Man's Wound' relates to what is happening today between the British and Irish nations. It is tragic that his wartime experiences should remain so pertinent but, nevertheless, those experiences are a source of guidance and encouragement to those who continue the struggle today.That book is one to convert the unbeliever and to inform the ignorant, just as Ernie O'Malley himself turned to republicanism at Easter 1916 when as a young medical student he witnessed Padraig Pearse reading the Proclamation outside the GPO in Dublin and then followed the subsequent events of the Rising.

His well-to-do family never discussed national politics at home - his elder brother was an officer in the British Army and died in that service, but Ernie devoted the best years of his life to the fight for the Irish Republic, so that in 1923 the Sinn Féin news-sheets claimed that he had '..perhaps the greatest individual record during the Tan War and was one of the bravest soldiers who ever fought for the independence of Ireland.'He wanted to show the struggle of a mainly unarmed people against the might of an 'empire' and his book pays constant tribute to the heroism of a risen people.

He was famed for his own courage, although like the truly brave he freely admitted to feelings of fear and inadequacy. Undeterred by mass condemnations from the British and their Irish allies, by newspapers and professional politicians and by the Catholic Hierarchy, between 1919 and 1921 the Irish Republican Army waged a war that also involved shooting 'policemen', executing British Officers, burning buildings, punishing spies and informers - in short, all those actions which Westminster and Leinster House vie with each other in condemning today. And Ernie O'Malley was very active in all such actions.

Ernie O'Malley was very active in attacks on British Army barracks, ambushes, raids and always in organisation and leadership crucial for the building of a people's army. He fought the Auxiliaries, an elite group of ex-BA officers attached to the RIC - a sort of 1920 SAS. He admitted that the RIC had "the guts to stick it out" but insisted "we can't admire Irishmen who fight for foreigners against us." His books are still useful handbooks for contemporary guerrillas.

A significant section of 'On Another Man's Wound' concerns his eventual capture by British forces in Inistioge, County Kilkenny, on 9th December 1920 (a notebook found on him had the names of all the members of the 7th Battalion IRA [Callan] of the West Kilkenny Brigade - many of whom were subsequently arrested) and the torture and imprisonment he underwent at the hands of the British Army, including his interrogation ordeal in Dublin Castle, the 'Castlereagh of the Tan War'.

Threatened with hanging for an action he did not commit, in the midst of brutal questioning, Ernie O'Malley replied - "With us, hanging is no disgrace." It is a revealing line, and one which puzzled his British torturers, who never will understand the mentality, motivation and moral strength of their opponents.

The prison chapters of his books illustrate how he and his comrades defied the prison system and bewildered their guards who, as O'Malley stated, "..had been told that we were murderers. That meant an image from a Sunday newspaper - twitching hands and furtive walk, or sullen hardness. They heard us laugh and sing, rag and annoy each other, joke and refuse to take prison regulations seriously.." But he pays tribute, too, to those who showed humanity to prisoners, which makes his verdicts on the others and on the British caste system all the more convincing.

After an historic escape from Kilmainham Jail on the 14th February 1921, Ernie O'Malley returned to the Martial Law areas and an intensified war campaign, until he was first baffled, then broken-hearted by the truce called in July 1921. One of the grimmest incidents had taken place one month previously, as Officer Commanding of the IRA Division involved, he had taken it upon himself to execute three captured British Army officers because "..any officers we capture in this area are to be shot until such time as you cease shooting your prisoners.."

He wanted the Irish Republican Army to have status abroad, rather than be hidden behind the image of a suffering colonial people. As he bluntly put it to his affronted superiors later in 1921 - "We (the IRA) had never consulted the feelings of the people. If so, we would never have fired a shot. If we gave them a good strong lead, they would follow."

If his books were required reading in schools and universities, instead of the shoneen or revisionist or simply non-existent versions of modern Irish history, then the people of Ireland would be better prepared to achieve a true independence. As he wrote of the best of the IRA recruits, in words that typify his own unyielding spirit - "At times one came across a man who had been born free. There was no explaining it. One just accepted and thanked God in wonder!"

Ernie O' Malley's two books are best read together : it is in 'The Singing Flame' that the British faces fade and are replaced by Irish counterparts and the high noon of summer darkens to the Mulcahy/Cosgrave years. Of course 'The Singing Flame' is partisan ; one intended by its author as support for the republican tradition - with the 'cult' of 1916 transformed into the 'cult' of 1922, where the Four Courts of Dublin stands in place of the GPO.

It is also an exciting story, full of incidents and answering some questions that had been posed for half a century ; relating his Civil War days as Assistant Chief of Staff in Dublin where he commanded future Fianna Fail ministers like Sean Lemass and Tom Derrig, while leading a hunted existence in a city resembling Belfast of the 1970's.

The second of the books also has clear lessons for today, containing many parallels and the same abuse and falsified arguments used against the republicans then as now. In the early days of the Civil War, Ernie O'Malley and his IRA Company heard a priest at Mass denounce them as looters and murderers : "The Hand of God was against us.." , according to the priest, he said. His officers wanted to walk out, but he motioned them to remain ;"If we were going to be insulted when we could not hit back, we might as well be dignified. It was good to get out in the fresh air again."

He could have accepted power and privilege under the Free State but he remained faithful to the Republic and rejected both the 1921 Treaty and de Valera's alternative Document No. 2. He told a Free State general, J.J. 'Ginger' O' Connell, at the time of the Treaty debates - "You'll have to fight in our area if you are false to your oath. That's where you'll meet with immediate and terrible war."The irony was pointed : Lloyd George had threatened an "immediate and terrible war" if the Treaty was not accepted.

True to his word, when the 1921 Treaty was ratified, Ernie O'Malley's Second Southern Division IRA was the first to renounce it : in the war against the Staters, Ernie O'Malley was (Acting) Assistant Chief of Staff to Liam Lynch and was also Officer Commanding of the Ulster and Leinster Commands. Liam Lynch was in the South/Cork area while Ernie O'Malley remained based in the enemy's stronghold of Dublin. He wrote of waging a guerrilla warfare that, this time, for him, was urban based rather than rural and, when asked by a journalist why the IRA were still fighting, he replied : "I think they think they're fighting for a younger generation." Ernie O' Malley was 24 years of age at that time.

He himself knew that he was fighting imperialists, both British and Irish varieties, and believed that the Free State Cabinet and a few Catholic bishops should not be immune from the war. He also recognised and acknowledged the great support given to the republican cause by Cumann na mBan and other Irish republican women, and one feature of his books is the courage, strength and involvement of such women. As he wrote - "During the Tan War the girls had always helped but they had never sufficient status. Now they were our comrades, loyal, willing and incorruptible comrades. Indefatigable, they put the men to shame by their individual zeal and initiative."

His book 'The Singing Flame' reveals much of Free State treachery and covers inside stories of the critical months before the IRA attack on the Four Courts began, and he paints a vivid picture of the war. But perhaps the most important pages are the prison chapters, detailing the scenes of prison life in Portobello Barracks, in Mountjoy, in Kilmainham Jail and in the Curragh internment camps, highlighting the deaths of comrades and the hunger-strike.

Despite his wounds (hit over 20 times by Free State gunfire), the threats of execution, and a wasting sickness worsened by forty-one days on hunger-strike, Ernie O'Malley was a leading challenge to "..the petty automatons that help to keep one captive..". Some of his most inspiring passages in 'The Singing Flame' concern that 'other war' that prisoners fought : in jail.

Then as now, Irish republican prisoners fought against criminalisation and for prisoner-of-war status : as Ernie O'Malley wrote - "Free men cannot be kept in jail, for their spirits are free. In our code, it is the duty of prisoners to prove that they cannot be influenced by their surroundings. Make the enemy feel a jailer but be free yourself."

An appendix of prison letters documents that spirit of defiance. Not surprisingly, O'Malley was the last republican leader to be released from the Curragh in July, 1924, although he had been confined to bed with his many wounds for most of his imprisonment : despite medical operations, he carried in his body five bullets to the grave.

When 'The Singing Flame' was published in 1978, twenty-one years after his death, the chief political book reviewer of 'The Irish Times' newspaper saw Ernie O'Malley as "..the unrepentant Fenian and perhaps even as the very first Provisional.." ('1169' comment : we disagree - O'Malley fought against the Free Staters and Westminster, he didn't administer political or military 'control' on their behalf.) Ernie O'Malley was one of the bravest, most idealistic, most dedicated and determined of socialist republican fighters, ruthless against imperialism, but chivalrous in war.

On the 30th June 1922, as Officer Commanding of his IRA Garrison, he most unwillingly surrendered the destroyed Four Courts in Dublin : when Free State officers accused him of deliberately causing the fire and the great explosion that had wrecked the building, he denied that republicans had set off a mine - "It was the spirit of freedom lighting a torch. I'm glad she played her part." Two years before he died he wrote - "The spirit of freedom is immeasurable and its strength can suddenly increase in unexpected ways."

The time will come when through that Spirit of Freedom the Irish Republic will not just be realised in the mind, and then the epitaphs of those like Ernie O'Malley and Bobby Sands and Francis Hughes can indeed, together with that of Robert Emmet, be truly written, as part of a living tradition.

Earnán Ó Máille ; 26th May 1897 – 25th March 1957.

(This is an edited version of an article we first posted here in 2008.)

'CHURCHILL...'

From 'The United Irishman' newspaper, April 1955.

Gone is the English control of the markets ; those countries - Japan, America, Russia, Germany - and those one-time subject states of the Empire are all in competition for raw materials and manufactured products. The time choosen to signify his intention to resign is also a significant matter not referred to in the international Press.

A few days after the release for publication of the 'Yalta Documents' by the Americans he decided it was time to go ; was his pride hurt that he was made to appear a minor figure of 'the big three'?

However - these are only speculations and not very important. The important thing is that he is going, but his going will bring no big changes in England's attitude to Ireland, just as his coming made no changes.

(END of 'Churchill' ; NEXT - 'Tomas MacCurtain Commemoration', from the same source.)

ON THIS DATE (10TH AUGUST) 100 YEARS AGO : WILSON'S EXECUTIONERS HANGED BY WESTMINSTER.

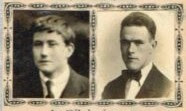

'(British Army) Field Marshall 'Sir' Henry Wilson (58) had returned to his home on Eaton Square, in London, after his 'jolly', on the 22nd June, 1922, but didn't notice that he had been followed home by, ironically, two veterans of that same 'Great War', Joe O'Sullivan (who had lost a leg at Ypres) and Reggie Dunne (pictured), both of whom were now IRA Volunteers. Before Mr Wilson could get from the taxi to his front door, he was shot dead.

Two policemen were shot and wounded trying to stop the IRA men from escaping and then a crowd of people jumped in to the melee in an attempt to deliver 'street justice' to the republicans, but more cops arrived to the scene and Joe and Reggie were arrested and charged with murder. They were hanged in August of that same year, 1922. RIP...' - from this blog, 22nd June 2022.

Joseph O'Sullivan and Commandant Reginald Dunne (Officer Commanding, Irish Republican Army, London) were two London-born veterans from the 'Great War' who became actively involved in the struggle for Irish independence in the heart of the enemy capital and, for their role in assassinating the Chief of the Imperial General Staff of the British Army and BA Military Advisor to the Stormont administration in Ireland (under James Craig), Field Marshall 'Sir' Henry Wilson, on the steps of his Belgravia home on 22nd June 1922, they were found guilty and sentenced to death at the Old Bailey.

They met their end together on the gallows of Wandsworth Prison on the 10th August 1922 - 100 years ago on this date.

Joseph O'Sullivan (25) was born in London of Irish parents, and had served in 'WW1' with the 'Munster Fusiliers'. He lost his leg below the knee in the fighting at Ypres, Belgium, was then employed as a clerk in Whitehall and he joined the London Brigade of the IRA in 1919.

Reginald Dunne (24) was born in England of Irish parents. He joined the British Army and fought with the 'Irish Guards' in France and, after leaving the British Army, he studied to become a teacher. Like his comrade, he joined the London Brigade of the IRA in 1919 and rose through the ranks to become second-in-command.

The republican operation itself was a success but their car and driver never made it to the scene, so both men tried to escape on foot. They were chased by a crowd of civilians and police for about half a mile and, on reaching Ebury Street, were caught by those chasing them and defended themselves as best they could - during the melee a policeman was shot dead. They were arrested and were hanged on the 10th August, 1922.

Both men (inset) are commemorated on a memorial in the Republican Plot in Deansgrange Cemetery Dublin (pictured).

Their remains were buried in Wandsworth Prison but, in July 1967, their bodies were repatriated to Ireland and reburied in the Republican Plot in Deansgrange Cemetery. May both of those brave Irish soldiers rest in peace.

'DIVIDED LOYALTIES...'

Ulster loyalism displayed its most belligerent face this year as violence at Belfast's Holy Cross School made international headlines.

But away from the spotlight, working-class Protestant communities are themselves divided, dispirited and slipping into crisis.

By Niall Stanage.

From 'Magill' magazine, Annual 2002.

"A lot of the loyalist communities, particularly in East and North Belfast, depended on the shipyard.." Davy Mahood says, "..a lot of people on the Shankill Road, for example, would have had a family history of working there. And then the whole thing collapsed around them. There was no work. It was devastating."

Many in the loyalist community react to these myriad setbacks, both real and perceived, with a sullen pessimism. Apathy to politics and politicians has spread wide and deep in a manner that was unimaginable just a decade ago. But militancy has its appeal too ; the largest paramilitary group, the UDA, has temporarily ceased recruiting, so swollen have its ranks become.

There are many possible motivations for joining the paramilitaries, a hatred of Catholics and a taste for violence included but, according to leading loyalist John White, the absence of any tangible peace dividend in working-class districts has been partly responsible for the current surge in membership... (MORE LATER.)

ON THIS DATE (10TH AUGUST) 47 YEARS AGO : DEATH OF A 'RELUCTANT SIGNATORY'.

'Robert Barton was an unlikely revolutionary coming from a landed and wealthy Protestant family who owned the well-known French wine company, Barton & Guestier ; his father was Charles William Barton and his mother was Agnes Childers. His wife was Rachel Warren of Boston, daughter of Fiske Warren and, hailing from such 'stock', he attended (as expected of him) Rugby School and then to Oxford University.

He served in the first World War where two of his brothers were killed. He was converted to Irish nationalism after the Easter Rising. Barton was the most reluctant Irish signatory of the Treaty and had to be cajoled to sign. He was faced on one side by Griffith, Collins and Duggan and on other by his cousin, Erskine Childers, the secretary of the Irish delegation, who urged him not to sign. His actions during the negotiations caused Lloyd George to describe him as that "pipsqueak of a man". Having signed the Treaty, Barton repudiated it during the Civil War and Childers was executed after being found in Barton's home with a firearm...' (From here.)

Robert Barton's (pictured) first cousin and close friend was Robert Erskine Childers, a man who was inadvertently to play a significent part in Mr Barton's death, as stated above.

On Monday, 5th of December 1921, in Downing Street in London, the then British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, announced to the Irish side in the 'Treaty' negotiations that he had written two letters, one of which would now be sent to his people in Ireland ; one letter told of a peaceful outcome to the negotiations, the other told of a breakdown in the negotiations - Lloyd George stated that if he sent the latter one "..it is war, and war within three days. Which letter am I to send?"

That 'War Letter' meeting took place, as stated, on the afternoon of Monday 5th December 1921 ; at around 7pm that same evening, Michael Collins and his negotiating team left that Downing Street meeting to discuss the matter between themselves and returned to Downing Street later that night. Collins and Griffith (both pro-Treaty) had pressurised their colleague, Robert Childers Barton (the Irish Minister for Economic Affairs) to accept the Treaty of Surrender, telling him that if he did not sign then he would be responsible for "Irish homes (being) laid waste and the youth of Ireland (being) butchered.." and, at about 11pm on Monday, 5th December 1921, Barton signed the document.

Ten days later (ie on the 15th December 1921) Barton (pictured) had this to say in relation to that eventful day -

"I want first of all to say we were eight and a half hours on that Monday in conference with the English representatives and the strain of an eight and a half hours conference and the struggle of it is a pretty severe one. One, when I am asked a question like that, "Was it or was it not?", I cannot give you an answer. But as regards particular aspects of that question, which I cannot take on oath, I can only give you my impression.

It is in my notes that the answer is given, and it is there because it was my impression of that conference. It did appear to me that Mr. Lloyd George spoke to me and I had an impression that he actually mentioned my name ; but I could not swear on oath that he mentioned my name, or actually addressed me when he spoke. It appeared to me that he spoke to me. What he did say was that the signature and the recommendation of every member of the delegation was necessary, or war would follow immediately and that the responsibility for that war must rest directly upon those who refused to sign the Treaty.."

On the 19th December that year, Barton, speaking in Leinster House, declared -

"I am going to make plain to you the circumstances under which I find myself in honour bound to recommend the acceptance of the Treaty. In making that statement I have one object only in view, and that is to enable you to become intimately acquainted with the circumstances leading up to the signing of the Treaty and the responsibility forced on me had I refused to sign. I do not seek to shield myself from the charge of having broken my oath of allegiance to the Republic — my signature is proof of that fact. That oath was, and still is to me, the most sacred bond on earth.

I broke my oath because I judged that violation to be the lesser of alternative outrages forced upon me, and between which I was compelled to choose. On Sunday, December 4th, the Conference had precipitately and definitely broken down. An intermediary effected contact next day, and on Monday at 3pm, Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins, and myself met the English representatives. In the struggle that ensued Arthur Griffith sought repeatedly to have the decision between war and peace on the terms of the Treaty referred back to this assembly. This proposal Mr. Lloyd George directly negatived.

He claimed that we were plenipotentiaries and that we must either accept or reject. Speaking for himself and his colleagues, the English Prime Minister with all the solemnity and the power of conviction that he alone, of all men I met, can impart by word and gesture — the vehicles by which the mind of one man oppresses and impresses the mind of another — declared that the signature and recommendation of every member of our delegation was necessary or war would follow immediately. He gave us until 10 o'clock to make up our minds, and it was then about 8.30. We returned to our house to decide upon our answer. The issue before us was whether we should stand behind our proposals for external association, face war and maintain the Republic, or whether we should accept inclusion in the British Empire and take peace..."

At about fifteen minutes past two on the morning of Tuesday 6th December 1921, Michael Collins and his team accepted 'Dominion status' and an Oath which gave "allegiance" to the Irish Free State and "fidelity" to the British Crown - the Treaty was signed and, on the 7th January 1922,the political institution in Leinster House voted to accept it, leading to a walk-out by then-principled members who, in effect, were refusing to assist in the setting-up of a British-sponsored 'parliament' in the newly-created Irish Free State.

The British so-called 'House of Commons' (401 for, 58 against) and its 'House of Lords' (166 for, 47 against) both ascribed 'legitimacy' to the new State on the 16th December 1921 - the IRA, however, at an army convention held on the 26th March 1922 (at which 52 out of the 73 IRA Brigades were present,despite said gathering having been forbidden by the Leinster House institution!) rejected the Treaty of Surrender, stating that Leinster House had betrayed the Irish republican ideal.

Within six months a Civil War was raging in Ireland, between the British-supported Free Staters and the Irish republicans who did not accept that 'Treaty'. And, today, the struggle continues to remove the British political and military presence from Ireland.

Robert Childers Barton, the 'Treaty of Surrender'-signatory who changed his mind on that treaty, was born in County Wicklow on the 14th March, 1881, and died in County Wicklow, at 94 years of age (the last surviving signatory of that failed treaty) on the 10th August, 1975 - 47 years ago on this date.

ON THIS DATE (10TH AUGUST) 132 YEARS AGO : DEATH OF PROLIFIC WRITER, POET AND REVOLUTIONARY JOHN BOYLE O'REILLY.

John Boyle O'Reilly (pictured) was born in the village of Dowth (Dubhadh), in the Boyne Valley in County Meath, on the 28th June, 1844 and, at 11 years young, got his first job with the 'Drogheda Argus' newspaper, where he stayed for four years.

He then travelled to the North of England and secured a position with 'The Preston Guardian' newspaper before returning to Ireland four years later, in 1863, at 19 years young, and joined the British Army.

His military training and associations brought him into contact with the Fenians and he became friendly with John Devoy, with whom he took the IRB Oath, but he was a member for less than a year when he was 'arrested' by the British and tried for treason - he was found guilty and, while imprisoned in Millbank Prison in London, was told that he was to be transported to Australia, which he was, on a ship called 'The Hougoumont'. Such was the hardships he endured, he attempted to end his own life but was saved by a fellow prisoner.

He escaped from that Australian prison in 1869, managed to get into England from where he secured transport to America. He 'disappeared' into the Irish community in Boston and got a job with 'The Pilot' newspaper and involved himself in, and fully supported, the 'Fenian Raids on Canada' and, working with John Devoy, planned the 'Catalpa Rescue'.

By then he was a published author and part-owner of 'The Pilot' and was known in Irish circles as 'a safe pair of hands' who could be trusted, politically and otherwise.

His fame as an author grew but fame and fortune didn't change him, politically - if anything, it gave him access to a 'society' he otherwise would not have had social contact with and he availed of those interactions to promote Irish republicanism.

His other works included 'Songs, Legends and Ballads', 'The Statues in the Block', 'The King's Men' and, in 1886, 'In Bohemia'. He published his 'Ethics of Boxing' in 1888 but died before he could go into print again ; he was only 46 years of age when he left this Earth in Hull, Massachusetts, in Boston, America, in 1890, on the 10th August - 132 years ago on this date.

John Boyle O'Reilly ; author, poet and Irish revolutionary, 28th June 1844 – 10th August 1890.

'NYC COMMITTEE.'

From 'The United Irishman' newspaper, March, 1955.

'From Irish Republican Prisoners Dependants Fund,

Clan na Gael HQ.

To General Secretary, Dublin.

A Cara,

Since last writing you our position has greatly strengthened, the GAA President, John (Kerry) O'Donnell, has given the 'Republican Aid Committee' (RAC) his very influential support.

He has obtained for us a special field day at Croke Park, with excellent matches to be played at same with permission to have a chance sale booth for the full season in the park, making a strong appeal on behalf of the prisoners at the GAA Banquet of the Year, besides giving generous personal contributions, and pledging full support on behalf of the Prisoners' Aid.

The group attached to the AOH branch Highbridge, the Bronx, who organised a very successful dance last year, are again to repeat their effort on April 16th, besides making a special subscription drive in their area.

The members of the branch have all declared their willingness and desire to help, and the Seán Oglaigh na hEireann Cumann have also expressed their desire to carry out the same work during May and to do so in co-operation with our committee.

All this within the first month of 1955 shows that we have made great progress in New York, due mainly to the activities of the Volunteer's of Omagh and Armagh. We expect that offers of help will be forthcoming from other sources, but the one great danger to the unity that is gradually coming about in New York is the toleration of groups who do not want to do work with or through our committee.

You have already received correspondence on this matter.

Hoping to hear from you soon,

C. McLoclainn,

Correspondence Secretary,

New York Committee,

Republican Aid Committee.'

(END of 'NYC Committee' ; NEXT - 'RAC Reminder', from the same source.)

ON THIS DATE (10TH AUGUST) IN...

...1719 :

On the 10th August, 1719, the British 'House of Commons' proposed that all 'unregistered' priests in Ireland should be branded on the cheek with a red-hot poker. The plan was ratified by the English ministry but was ultimately abandoned.

This barbarism was a follow-on from the earlier so-called 'Penal Code' law, under which all 'unregistered Catholic clergy' were ordered "...to depart out of this kingdom before the first day of May, 1698..". That 'law' applied to "...all archbishops, bishops, vicars-general, deans, Jesuits, monks, friars, and all other regular Popish clergy, and all Papists exercising ecclesiastical jurisdiction.."

The penalty for non-compliance was imprisonment without bail until such time as the 'offenders' could be transported 'beyond the seas'. Any Popish archbishop, bishop etc who came into Ireland after the 9th December 1697 was, if caught by the 'authorities', liable to twelve months imprisonment followed by 'transportation beyond the seas'.

Those who returned to Ireland, having being 'banished', were to be judged as "...traytors, to suffer, lose, and forfeit, as in the case of high treason.." - they were half-hanged, disembowelled while still living, and then quartered.

We're not big into any religion on this blog, but that's a bit too much, even for us!

======================================

...1922 :

On the 10th August, 1922, the Free Staters carried out major offensives in the Cork and Tipperary areas ; faced with superior numbers and firepower, the IRA abandoned infrastructure in Cork city (including 'Charles Fort'), but ensured the buildings they were leaving were left uninhabitable. The Staters reportedly lost at least eight of their number at Rochestown and Douglas, such was the resistance they met.

The town of Clonmel, in Tipperary, was taken into Free State control when Leinster House-supported General John T. Prout (a republican-gamekeeper-turned Free State-poacher) and his troopers took the town from the IRA. The Staters appeared not to trust their man Prout fully, however - a State memo issued in October 1922 described him as "...too weak as well as too guilless to handle traitorous or semi-mutinous incompetents.." , by which was meant those State troopers who, although wearing the FSA uniform, might not have been heart-and-soul in support of the new State and the manner in which it conducted itself.

And even though Prout and his State bandits were responsible for the deaths of, among others, Dinny Lacey and Liam Lynch, his conduct was criticised by his own 'GHQ' after the Stater 'victory' over Irish republicans, with special emphasis placed on his failure to stamp out guerrilla activity in County Wexford.

Prout was demobilised from the FSA in June 1924, and had by then obtained the rank of 'Major General'. His military boss, Richard Mulcahy (who, like Prout, was a republican-gamekeeper-turned Free State-poacher) acknowledged that Prout generated mixed feelings (!) - "I think that is a very regrettable matter. Major-General Prout has been made the butt of an attack by a none too sober and none too industrious section here in the country and it is a most disconcerting matter that an officer of Major-General Prout's record and service during the last 18 months or two years finds himself now demobilised.."

The demobilised FSA Major-General died in 1969 in Chesterfield, New Hampshire, and is buried in Brattleboro, Vermont, in America. Some consider him to be a war hero.

======================================

...1922 :

The Hudson family, from Carroll's Cottages in Glasthule, County Dublin, were well-regarded locally and further afield as republican operatives, who could trace their rebel origins back to the 1916 Easter Rising and beyond.

Joe 'Sonny' Hudson (18, pictured) was a Volunteer with 'B Coy', 2nd Battalion of the Dublin No. 2 Brigade, IRA, and was at home on the evening of Thursday, the 10th August, 1922, when the house was raided by Free State forces. He had no time or chance to escape, and put his hands in the air, surrendering. A Stater shot him in the stomach, and he died from the wound on the 12th August.

It was later declared by the State that an automatic pistol was found beside him but, on examination, it was found to be loaded with ammunition of the wrong calibre, meaning that the weapon could not have been fired. 'Planted' at the scene, no doubt.

======================================

=======================

=======================

Thanks for the visit, and for reading!

Sharon and the team.

Wednesday, August 10, 2022

IRELAND, 1922 - AUTOMATIC PISTOL, WRONG AMMUNITION : 'PLANTED' BY STATERS.

Labels:

Agnes Childers,

Bernard Stuart,

Earnán Ó Maille,

Fiske Warren.,

Joe Sonny Hudson,

John Boyle O'Reilly,

John T. Prout,

Joseph O'Sullivan,

Rachel Warren,

Reginald Dunne,

Republican Aid Committee

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)