Wednesday, April 24, 2024

1921, DUBLIN, CONFUSED CONTACT - RIC VERSUS BRITISH FUSILIERS...

In April, 1919, the issue of support for the RIC, the pro-British 'police force' in Ireland, was being discussed by the public and by their representatives in (the 32-County) Dáil Éireann.

On the 23rd April that year, the formal response of the Dáil on that issue was finalised and approved by the Deputies, and was made known to the public the next day (the 24th April 1919) -

"(The RIC and DMP should be treated as) persons who, having been adjudged guilty of treason to their country, are regarded as unworthy to enjoy any of the privileges or comforts which arise from cordial relations with the public.

(They) must receive no social recognition from the people, no intercourse is permitted with them, they should not be saluted or spoken to in the streets not their salutes returned.

They should not be invited to nor received in private houses as friends or guests, they should be debarred from participation in games, sports, dances and all social functions conducted by the people.

In a word, they should be treated as persons who have been adjudged guilty of treason to the country..."

Those 'cops' have changed uniforms since then - been rebranded - but that penalty remains apt.

==========================

ON THIS DATE (24TH APRIL) 108 YEARS AGO : "A TERRIBLE BEAUTY IS BORN..."

Pictured - Pádraig Pearse, Thomas J Clarke and Thomas MacDonagh.

The 1916 Easter Rising began, in Ireland, on Easter Monday, 24th April 1916 and lasted for six days. The official surrender occurred on Friday, 28th April, and all fighting ceased on Saturday 29th April.

The rebels numbered around 2500 ; by the end of the fighting, there were around 20,000 British troops in Dublin.

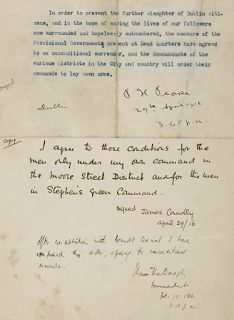

On the 29th April 1916, a republican 'surrender document' was circulated between the combatants, which read -

'In order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin civilians and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered, the members of the Provisional Government present at headquarters have agreed to an unconditional surrender, and the commandants of the various districts in the City and county will order their commands to lay down arms..'

The document (above) was signed by, among others, Patrick Pearse and Thomas MacDonagh, and it signalled the end of six days of fighting between approximately 20,000 British troops (including, in their ranks, Irish men) and a volunteer rebel force of about 2,500 Irish men and women (and other nationalities).

At about 3.45pm on Saturday, 29th April 1916, the Rising was brought to an end - Pádraig Pearse surrendered to British Brigadier-General Lowe, James Connolly surrendered on behalf of the 'Irish Citizens Army' and Ned Daly surrendered to British Major De Courcy Wheeler.

It is not mentioned as often as it should be, but before the surrender of Ned Daly and his forces, all of whom fought bravely in the North King Street area of Dublin, the British Officer who was in command of that particular engagement, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Taylor of the South Staffordshire Regiment, had lost 11 of his men with a further 28 having being wounded.

Following the surrender of Daly and the Dublin 1st Battalion, Taylor - who was to claim later that he was acting under orders from his superior, Brigadier-General William Henry Muir Lowe - ordered his men, who were enraged over having lost so many of their number, to 'flush out' any remaining enemy forces.

Taylor's troops began breaking into local houses and, before their bloodlust was satisfied, they shot and/or bayoneted 15 boys and men to death, all of whom were 'rebel fighters', according to the British.

Approximately 590 people died during the six days of the 1916 Rising, of which 374 were civilians (including 38 children, aged 16 or younger), 116 British soldiers, 77 Irish rebel soldiers and 23 members of the British 'police force' which operated in Ireland at that time ('1169' comment - the objective has not yet being obtained, as not one of those rebel/dissident fighters took up arms to 'achieve' a so-called 'Free State' : the aim then, as now, is to secure a Free Ireland).

Padraig Pearse, Tom Clarke and Thomas MacDonagh, three of those in command of the republican dissidents during the Rising, were court-martialed by the British on the 2nd May 1916 and sentenced to death and, the next day - 3rd May 1916 - they were taken to the Stonebreakers' Yard in Kilmainham Jail and, at dawn, were shot dead by a British Army firing squad.

It was these executions that prompted British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith (pictured) to warn General Maxwell that 'a large number of executions would sow the seeds of lasting trouble in Ireland' - that was the Westminster elite once again missing the point in regards to their 'Irish outpost' : 'lasting trouble in Ireland' is, unfortunately, guaranteed by the fact that it is the British military and political presence here that brings 'trouble', not the manner in which that presence treats its 'subjects'.

Before he was executed, Padraig Pearse stated :

"We seem to have lost. We have not lost. To refuse to fight would have been to lose ; to fight is to win. We have kept faith with the past, and handed on a tradition to the future. If you strike us down now, we shall rise again and renew the fight. You cannot conquer Ireland. You cannot extinguish the Irish passion for freedom. If our deed has not been sufficient to win freedom, then our children will win it by a better deed..."

Pádraig Pearse was born in Dublin on the 10th November 1879 to an English father (who worked as a sculptor) and an Irish mother, both of whom encouraged him to learn about and appreciate his roots. At 21 years of age he joined the 'Gaelic League' and his enthusiasm ensured his advancement within that organisation - he was appointed as the editor of their newspaper, 'An Claidheamh Solais' ('The Sword of Light').

Not content with just a newspaper from which to voice his pro-Irish opinion, he founded a school - St. Enda's College in Dublin, at 29 years of age, and structured its curriculum around Irish traditions and culture and tutored in both the Irish and English languages.

It was through the League that Pearse met like-minded individuals who also wanted 'to break the connection with England'.

At 35 years of age, in 1914, he was accepted as a member of the supreme council of the 'Irish Republican Brotherhood' (IRB), a militant group that had stated its intention to use force to remove the British military and political presence from Ireland and, during the 1916 Rising - which he was heavily involved in organising - he was in command of the General Post Office (GPO) in Dublin.

He was executed at dawn by a British Army firing squad on the 3rd May 1916, in the Stonebreakers' Yard in Kilmainham Jail.

'The Mother'

By Pádraig Pearse.

I do not grudge them : Lord, I do not grudge

My two strong sons that I have seen go out

To break their strength and die, they and a few,

In bloody protest for a glorious thing,

They shall be spoken of among their people,

The generations shall remember them,

And call them blessed.

But I will speak their names to my own heart

In the long nights;

The little names that were familiar once

Round my dead hearth.

Lord, thou art hard on mothers :

We suffer in their coming and their going ;

And tho' I grudge them not, I weary, weary

Of the long sorrow. And yet I have my joy :

My sons were faithful, and they fought.

Tom Clarke was born in a British military camp at Hurst Park in the Isle of Wight, on the 11th March 1858.

His father was then a Corporal in the British Army but, like Tom's mother, was Irish born. A year later Corporal Clarke was drafted to South Africa where the family lived until 1865. Tom first saw Ireland about 1870, when his father was appointed a Sergeant of the Ulster Militia and was stationed at Dungannon in County Tyrone.

It was there that he grew to early manhood, and his father wished him to follow in his own footsteps and join the British Army, but the 'Poor Old Woman' had already enlisted Tom in her own small but select Army, at a time when the prospects of putting food on the table were not good - an Gorta Mór and the defeat of the Fenians still hung heavy over the land. Tom Clarke was sworn into the 'Irish Republican Brotherhood' by Michael Davitt and John Daly ; he could have had no more worthy sponsors.

In 1880, at twenty-two years young, he emigrated to the United States where he joined Clann na Gael and quickly volunteered for active service in Britain. The ship he travelled on struck an iceberg and sank, but he was rescued and landed on Newfoundland. Resuming his interrupted journey, he reached London where he was soon arrested - he had been followed from New York by 'Henri Le Caron', a British spy.

On 14th June 1883, at the 'Old Bailey', he was, with three others, sentenced to penal servitude for life.

For 15 years and nine months, in the prisons of Chatham and Portland, Tom Clarke endured imprisonment without flinching ; 15 years and nine months of an incessant attempt, by the British, to deprive him of his life or reason. This torture did not cease with daylight and recommence on the following day ; it was maintained during the hours of darkness when even the vilest criminal was entitled to sleep and rest.

But Tom Clarke and his comrades got neither sleep nor rest - cunning devices for producing continuous disturbing sounds were erected over their cells - these are described in his book 'Glimpses of an Irish Felon's Prison Life' . The relentless brutality at length drove two of his comrades, Whitehead and Gallagher, hopelessly insane.

With John Daly, they were released in 1896 ; Daly had been arrested a year after Tom Clarke, and had hitherto shared the same prisons with him ; though kept apart, they had managed to communicate with each other now and again. The release of his friend was a sore loss to Tom Clarke who, for a further two years, had to endure alone an even more intensified form of torture.

Released in 1898, aged 40, he spent a short time in Limerick with his friend John Daly before returning to America where, in 1901, he married Kathleen Daly, John Daly's daughter.

With Devoy, he founded the 'Gaelic American' newspaper and, as its assistant editor, worked in New York until 1907. Then he returned to Ireland and opened a newspaper shop at Parnell Street, Dublin, which quickly became the meeting place for Pádraig Pearse and that valiant company of a new generation who weren't prepared to wait for crumbs from the British table.

They knew Tom Clarke as a man who had for so long been tested in the crucible of suffering and had been found unbreakable, and he didn't fail them.

In 1916, they repaid him by insisting that his should be the first signature to the Proclamation of the Republic ; it was the greatest day of his life, though well he knew it meant for him the end.

He was shot on the 3rd May 1916, at 58 years of age, of those only eighteen had been spent in Ireland. If a man is judged by the life he has led then there is no more splendid figure than Tom Clarke ; the onset of the years chills the blood of most men - add to this the incredible physical and mental torture which he had endured for almost sixteen of those years. Most of the remainder were years of hardship and disillusionment.

His father's influence and his early environment militated against his faith yet, like Padraig Pearse, he turned his back on 'the beautiful vision of the world', and set his face to the road before him, the road indicated by 'the Poor Old Woman'.

On the 1st February 1878 a child, Thomas, was born in Cloughjordan in Tipperary, into a household which would consist of four sons and two daughters - the parents, Joseph and Mary (Louise Parker) MacDonagh, were both employed as teachers in a near-by school.

He went to Rockwell College in Cashel, Tipperary, where he entertained the idea of training for the priesthood but, at 23 years of age, decided instead to follow in his parents footsteps and trained to be a teacher.

He obtained employment at St Kieran's College in Kilkenny and, while working there, advanced his interest in Irish culture by joining the local 'Gaelic League' group and was quickly elected to a leadership role within that organisation but, by 1905, he had left the League and moved on to teach at St Colman's College, Fermoy, where he also established himself as a published poet.

Three years later he moved to a new position, as resident assistant headmaster at St Enda's, Pádraig Pearse's school, then based in Ranelagh, Dublin. In 1911, after completing his BA and MA at UCD, he was appointed lecturer in English at the same institution. In 1912 he married Muriel Gifford, sister of Grace, who would later marry Joseph Plunkett in Kilmainham Gaol.

In the years prior to the 1916 Rising MacDonagh became active in Irish literary circles and was a co-founder of the Irish Review and, with Plunkett, of the Irish Theatre on Hardwicke Street. MacDonagh was a witness to Bloody Sunday in 1913 and this event appears to have radicalised him so much so that he moved away from the circles of the literary revival and embraced political activism.

He joined the Irish Volunteers in December 1913 and was appointed to the body's governing committee. In 1914 he rejected John Redmond's appeal for the Volunteers to join the fight in the First World War. On the 9th September 1914 he attended the secret meeting that agreed to plan for an armed insurrection against British rule. By March 1915 he had been sworn into the ranks of the 'Irish Republican Brotherhood' and was also serving on the central executive of the Irish Volunteers, was director of training for the Volunteers and commandant of the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade.

In 1916, at the age of 38, he joined his comrades in challenging a then world power, England, over the injustices which that 'world leader' was inflicting in Ireland and, with six of his comrades, he signed a proclamation declaring the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies, free of any external political or military interference.

He was found guilty by a British court martial that followed the 1916 Rising, and was sentenced to death. He was executed by firing squad on the 3rd May that year. His friend and fellow poet Francis Ledwidge wrote a poem in his honour after his death ; Ledwidge, the 'Poet of the Blackbirds', fought for the British in the 'First World War' and was injured in 1916 - he was recovering from his wounds in hospital when news reached him of the Rising and he let it be known that he felt betrayed by Westminster over its interference in Ireland -

Lament for Thomas MacDonagh.

He shall not hear the bittern cry

In the wild sky where he is lain

Nor voices of the sweeter birds

Above the wailing of the rain.

Nor shall he know when loud March blows

Thro' slanting snows her fanfare shrill

Blowing to flame the golden cup

Of many an upset daffodil.

And when the dark cow leaves the moor

And pastures poor with greedy weeds

Perhaps he'll hear her low at morn

Lifting her horn in pleasant meads.

In his address to the court martial, Thomas MacDonagh said -

"Gentlemen of the court martial, I choose to think you have done your duty according to your lights in sentencing me to death. I thank you for your courtesy. It would not be seemly for me to go to my doom without trying to express, however inadequately, my sense of the high honour I enjoy in being one of those predestined to die in this generation for the cause of Irish freedom. You will, perhaps, understand this sentiment, for it is one to which an Imperial poet of a bygone age bore immortal testimony : "T'is sweet and glorious to die for one's country."

You would all be proud to die for Britain, your Imperial patron, and I am proud and happy to die for Ireland, my glorious fatherland...there is not much left to say. The Proclamation of the Irish Republic has been adduced in evidence against me as one of the signatories. I adhere to every statement in that proclamation. You think it already a dead and buried letter - but it lives, it lives! From minds alive with Ireland's vivid intellect it sprang, in hearts alive with Ireland's mighty love it was conceived. Such documents do not die.

The British occupation of Ireland has never for more than one hundred years been compelled to confront in the field of flight a rising so formidable as that which overwhelming forces have for the moment succeeded in quelling. This rising did not result from accidental circumstances. It came in due recurrent reasons as the necessary outcome of forces that are ever at work.

The fierce pulsation of resurgent pride that disclaims servitude may one day cease to throb in the heart of Ireland — but the heart of Ireland will that day be dead. While Ireland lives, the brains and brawn of her manhood will strive to destroy the last vestige of foreign rule in her territory. In this ceaseless struggle there will be, as there must be, an alternate ebb and flow.

But let England make no mistake. The generous high-bred youth of Ireland will never fail to answer the call we pass on to them, will never full to blaze forth in the red rage of war to win their country's freedom. Other and tamer methods they will leave to other and tamer men ; but for themselves they must do or die. It will be said our movement was doomed to failure. It has proved so. Yet it might have been otherwise.

There is always a chance of success for brave men who challenge fortune. That we had such a chance, none know so well as your statesmen and military experts. The mass of the people of Ireland will doubtless lull their consciences to sleep for another generation by the exploded fable that Ireland cannot successfully fight England.

We do not propose to represent the mass of the people of Ireland. We stand for the intellect and for immortal soul of Ireland. To Ireland's soul and intellect, the inert mass drugged and degenerated by ages of servitude must in the destined day of resurrection render homage and free service receiving in turn the vivifying impress of a free people.

Gentlemen, you have sentenced me to death, and I accept your sentence with joy and pride since it is for Ireland I am to die.

I go to join the goodly company of men who died for Ireland, the least of whom is worthier far than I can claim to be, and that noble band are themselves but a small section of the great, unnumbered company of martyrs, whose Captain is the Christ who died on Calvary. Of every white robed knight of all that goodly company we are the spiritual kin.

The forms of heroes flit before my vision, and there is one, the star of whose destiny chimes harmoniously with the swan song of my soul. It is the great Florentine, whose weapon was not the sword, but prayer and preaching ; the seed he sowed fructifies to this day in God's Church. Take me away, and let my blood bedew the sacred soil of Ireland. I die in the certainty that once more the seed will fructify."

Thomas MacDonagh - born on the 1st February 1878, executed by Westminster on the 3rd May 1916.

The 1916 Rising is one of the most important events in the history of this exceptional country and, despite the efforts of some, there are still people like us who will always strive to keep our country exceptional, from all threats, foreign and domestic.

'SINN FÉIN REPLIES TO MR. HANNA...'

From 'The United Irishman' newspaper, April 1955.

Sinn Féin is the civilian or political arm of the Republican Movement and it therefore intends to use all constitutional means at its disposal for the achievement of its objectives - the primary object being the re-enthronement of a 32-County Republic.

In the 26-County State it intends to make use of the Leinster House elections in order to have its candidates elected by the people to a 32-County Dáil ; not to Leinster House.

In the Six-County State it would normally make use of the Stormont elections for the same purpose. However, it is prevented from doing this by a regulation of the Stormont regime which states that before anyone is allowed to go forward as a candidate in the elections in the Six County area they must sign a declaration that they will take their seats in Stormont if elected.

Since Sinn Féin candidates have no intention of sitting in Stormont any more than in Leinster House they could not honourably sign such a declaration...

('1169' Comment : Irish republicans continue to operate an abstentionist policy in regards to Stormont and Leinster House, but there are still individuals and groups in this State and in Ireland [for instance, Fianna Fáil and Provisional Sinn Féin] who consider themselves to be 'republican' yet are quite content to sit in one or other, or both, partitionist assemblies.)

(MORE LATER.)

In 1920, an RIC Detective named Swanton had made a name for himself in Ennis, County Clare, where he operated as part of a two-person Detective team for the English Crown.

Mr Swanton viewed his position as a vocation, rather than just as a 'job' to pay the rent, and was said to be "...most zealous in trying to track down any type of movement on the part of the IRA..."

His eagerness had brought him to the notice of IRA HQ in Dublin, and an order was sent to the IRA in County Clare to deal with the man. It was known that, on the 24th April, himself and his colleague would be walking pass a Christian Brothers School, towards a crossroads, having paid a visit to the local railway station.

The information was correct in regards to the locations and times given, but the Detective was on his own, and had been 'tailed' on his walk by an IRA man, Tom Keane, who had kept his distance from Mr Swanton.

However, Mr Swanton, being ever cautious, spotted the IRA Volunteer behind him and ran towards the crossroads - where four other Volunteers (Liam Stack, Nick Foley, Peter O'Loughlin and William McNamara) were waiting for him.

The RIC Detective changed his route and kept running as two shots were fired at him ; he fell to the ground, motionless and, after observing from a distance for a few minutes, the IRA men moved off, satisfied that they had carried out their mission.

They were to learn later on that night that Mr Swanton, although badly wounded, was expected to recover, which he did...

==========================

On the 17th November, 1919, a number of bank officials left the Munster and Leinster Bank and the National Bank in the Millstreet area, County Cork, at about 8am, in a car and a horse-drawn carriage, to attend a cattle fair at Knocknagree in that county.

The bank officials were carrying a total of £16,700 between them, a huge amount of money in those days, which would be worth at least half a million Euro today.

Both vehicles were held-up by at least five armed men and the money was taken.

On the 24th April, 1920, Liam Lynch, Officer Commanding of the Cork No 2 Brigade IRA, accompanied by between 100 and 200 Volunteers, representing the Irish Republican Police, arrived in Cork to investigate the robbery and, a short time later, the Republican Police arrested eight men, seven of whom confessed to have been involved in the robbery.

£10,000 was recovered and the seven arrested men were sentenced to various lengths of deportation from, or exile within, Ireland ; more here.

==========================

SO, FAREWELL THEN, CELTIC TIGER....

It had to happen, sooner or later.

Most of the pundits and economists were too busy singing the Celtic Tiger's praises to notice, but a few critical observers worried all along about the weaknesses of a boom economy that depended so much on a few companies from one place - the United States.

By Denis O'Hearn.

From 'Magill' Annual 2002.

Productivity in the three US-dominated sectors grew by 215 per cent in the 1990's, nearly nine per cent annually.

In services, construction and basic manufactures, output per employee grew by just one per cent annually, which most experts would call stagnation.

In 1999, the average worker in a foreign company produced output worth nearly eight times more than the average worker in an Irish company.

Transnational corporate profits in Ireland rose spectacularly during the 1990's ; by the end of the decade, TNC's received six times more in profits than they had in 1990.

Meanwhile, Irish firms received less profits than they had in 1990, and this was reflected in a sharp rise in the number of company failures...

(MORE LATER.)

In April, 1921, the Officer Commanding of the West Clare Brigade IRA, Seán Liddy (pictured, a republican-gamekeeper-turned Free State-poacher) and Michael Brennan (...also a republican-gamekeeper-turned Free State-poacher) agreed to share resources in an attack on British forces in the West Clare area.

On the 24th April, Seán Liddy, Michael Brennan, Stephen Madigan, Michael McMahon and Liam Haugh took command of a combined force of IRA Volunteers and attacked the enemy in the Kilrush area of County Clare in the RIC Barracks, the British Army Barracks and the Coastguard Station, with no republican casualties.

One RIC member, a 'sergeant', was killed and others wounded, as were a few British Army soldiers and, in retaliation, their colleagues in the Crown Forces drove to the village of Monmore, in County Wexford, placed explosives in and around the home of IRA Volunteer Liam Haugh, and detonated them, destroying the house.

However, in the explosion, a splinter injured a British Army soldier and he died from his wounds later that same week.

Also, on this date - 24th April 1921 - an RIC patrol was ambushed by the IRA in Ennistymon, in County Clare, and one of the patrol was wounded and, near the town of Ennis, in the same county, an RIC man was shot at.

==========================

On the 24th April, 1921, three RIC members were driving in an unmarked car towards Cloghran Crossroads in North Dublin at the same time as a lorry carrying members of the British Army's Lancashire Fusiliers (pictured) were driving towards it.

Shots were fired from each vehicle and an RIC member, 'District Inspector' Michael Joseph Cahill ('Service Number 72022'), was badly wounded ; apparently, each group thought that the other was an IRA patrol, and opened fire!

Mr Cahill, from Clonmel, in County Tipperary, died from his wounds the following morning. He was a British 'Serviceman' who fell foul (!) of the 'Reduction In Force' legislation and moved 'sidewards' into the RIC ; he was stationed in Gormanstown Camp, in County Meath, and is buried in Shanavine, in Clonmel, in County Tipperary.

==========================

In 1914, 17-years-young John Beets 'Johnny' Bales, from Norfolk, in England, signed up with the 'Norfolk Yeomanry' (pictured) and was sent to Gallipoli and also 'kept the peace' (!) in Egypt.

He later 'adventured' with the 'Royal Air Force' in Salonika, and then returned to his home.

Seeking more 'adventure', he travelled to Ireland and, on the 30th March, 1921, he joined the RIC, as a member of 'P Company' of the Auxiliary Division, based in Tubbercurry, in County Sligo.

On the 22nd/23rd April, 1921, 'Cadet' Bales and a colleague ('Cadet' Bolam) were sent to Belfast on 'escort duty' and were spotted at about 9pm, at the junction of Donegall Place and Fountain Lane in the city, by two Volunteers from the Belfast Brigade ASU IRA, Séamus Woods and Roger McCorley, who attacked them.

'Cadet' Bolam was shot dead and John Bales was badly wounded ; he died in hospital at about 11pm on the 24th April, 1921.

==========================

BEIR BUA...

The Thread of the Irish Republican Movement from The United Irishmen through to today.

Republicanism in history and today.

Published by the James Connolly/Tommy O'Neill Cumann, Republican Sinn Féin, The Liberties, Dublin.

August 1998.

('1169' comment - 'Beir Bua' translates as 'Grasp Victory' in the English language.)

ROBERT EMMET AND THE IRELAND OF TODAY...

"For Emmet, finely gifted though he was, was just a young man with the same limitations, the same self-questionings, the same falterings, the same kindly human emotions surging up sometimes in such strength as almost to drown a heroic purpose, as many a young man we have known.

And his task was just such a task as many of us have undertaken : he had to go through the same repellent routine of work, to deal with the hard, uncongenial details of correspondence and conference and committee meetings ; he had the same sordid difficulties that we have, yea, even the vulgar difficulty of want of funds.

And he had the same poor human material to work with, men who misunderstood, men who bungled, men who talked too much, men who failed at the last moment.

Yes, the task we take up again is just Emmet's task of silent unattractive work, the routine of correspondence and committees and organising.

We must face it as bravely and as quietly as he faced it, working on in patience as he worked on, hoping as he hoped : cherishing in our secret hearts the mighty hope that to us, though so unworthy, it may be given to bring to accomplishment the thing he left unaccomplished, but working on even when that hope dies within us..."

(MORE LATER.)

On the 24th April, 1922, the 'Labour Party' and the 'Trade Union Congress' (ILP/TUC) held a general strike and protest against 'militarism and the prospect of civil war' in Ireland.

It was common knowledge that a fight was brewing between the forces of the Westminster-backed Free Staters and the IRA and the pro-Treaty of Surrender 'Labour Party' were as compelled then as they are now to accept a 26 County State rather than a Free Ireland, which would still have to be fought for.

Tens of thousands of Irish citizens attended a rally in O'Connell Street, in Dublin, as expected, as no one wanted a civil war ; the organisers had stated they were protesting against "...the growth of the idea that the military forces may take command of the civil life of the nation without responsibility to the people ; that military men may commit acts of violence against civilians and be immune from prosecution or punishment ; that possession of arms is the sole title to political authority.." which was, in effect, a pro-Leinster House/Free State mantra.

The 'strike' began in Beresford Place at 6am and finished at 9pm that night in O'Connell Street (then known as 'Sackville Street') where three stage units had been erected to allow for speeches to be delivered by trade union affiliated speakers, Thomas Johnson, Cathal O'Shannon and Edward O'Carroll.

==========================

April, 1922 - the whole of Ireland was in political and military turmoil due, firstly, to the continuing British political and military presence in the country and, secondly, because of the latest offer of a 'Treaty' to the Irish from Westminster.

Among other instances of injustice that month in 1922 were the introduction of the 'Special Powers Act' and the Arnon Street murders, where six Catholic civilians were shot or beaten to death by men who broke into their homes.

'The Irish News' newspaper, a somewhat Irish nationalist publication at the time, published an Editorial on the 24th April, 1922, in which the newspaper held the Stormont Administration (and, by extension, the Westminster Parliament in London) responsible for the murderous misdeeds -

"Not a single honest official effort had been made to get at the truth about these ghastly occurrences...full responsibility for all these hideous deeds of terrorism and blood rests on the shoulders of the established Government of this city...their failure to preserve a semblance of law and order is apparently complete.."

That news outlet (and practically all other such outlets in the country) has long since changed its political outlook to lay blame for all such political turmoil firmly at the feet of those who continue to strive for a proper political solution to the foreign and domestic butchery inflicted on us.

==========================

On the 24th April, 1922, William Sibberson (31) was working at his desk in Richardson's Chemical Company in the Short Strand, in Belfast, when he was shot dead.

On that same date, a 70-year-old man, Mr James Corr, who lived at 33 Lowry Street in Belfast, was shot dead by a loyalist gunman as he delivered coal in Middlepath Street in that city, and William Steele and Ellen Greer died of injuries received in an earlier incident ; Mr Steele, from Disraeli Street, and M/s Greer, from Enniskillen Street, were 'killed by a revolver belonging to her brother-in-law, an 'A Special'...'

==========================

The British Forces base in Celbridge, in County Kildare, was located in the well-fortified Mill complex, and was strengthened by RIC members from the various barracks that had been vacated as a result of IRA attacks on them and, later, due to the acceptance of the 'Treaty of Surrender' ; indeed, by the summer of 1920, it was the only RIC barracks remaining open in North Kildare.

In April, 1922, the British forces were ordered to vacate the building in Celbridge and hand it over to the Free State military, sometimes referred to in those early-Free Stater years as 'the Regular IRA' or the 'IRA' ; some of their operatives had actually been involved in the fight against the British and still enjoyed describing themselves as the 'IRA' even though, by then, the British Army shared their objectives.

On the 24th April, 1922, at about 11.30pm, the (proper!) IRA attacked the Staters in their barracks and a gunfight ensued for about an hour, during which the IRA Volunteers attempted to scale the walls of the building.

The attack was unsuccessful and the IRA withdrew from the scene.

==========================

'April 1 1924 -

Mr J H Thomas, British Colonial Secretary, assured Mr Cahir Healy, MP, that he was "aware of the feeling which existed" in Ireland over "the delay in setting up the Boundary Commission provided for in Article 12 of the Irish Treaty signed on December 6th, 1921".

The representative of Tyrone had asked whether Mr Thomas had knowledge of that dissatisfaction: and the minister had. But Mr Healy also asked the minister to say "if he was yet able to fix the date for a resumption of the conference" : and the reply to this part of the composite query was "As my hon. friend is aware, I am dealing with it".

Of course, no-one knows how much Mr Cahir Healy knows of Mr Thomas’s intentions; but if the Irish member is aware of nothing beyond the fact that the Welsh minister of the Crown is still "dealing" with a question that arose in January 1922, the extent of his information is not exactly voluminous.

Mr Healy wanted a date ; Mr Thomas neither fixed one nor indicated that he had one in his mind.

In fact, he said nothing that the Duke of Devonshire could not have said a year ago with equal regard for the truth and disregard for Irish feelings and interests.

As Mr Healy did not insist on a definite reply to a plain question, perhaps he is aware of some facts unknown to the public on this side of the Irish Sea ; but his effort to secure a statement worth twopence was not successful...' (From here.)

However, despite the nonchalance reluctance on the part of Westminster to abide by an agreement they freely entered into (in 1921!), a 'Boundary Commission Conference' was arranged for the 24th April, 1922.

It was held on that date, but collapsed, fruitless, on the 25th!

William Thomas Cosgrave, the 'President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State', was to later declare that he was pessimistic of the negotiations achieving anything because of James Craig's position ie - 'the longer the Boundary Commission could be delayed, the less likely that it would ever be formed at all'.

On the 26th April, 1924, the Free State government requested (!) the British Government to take immediate steps to constitute the Boundary Commission and, as Mr Craig continued to refuse to appoint a Commissioner to the body, the British threatened to refer the matter to the 'Judicial Committee of the Privy Council', thus buying themselves more time to do nothing!

==========================

Thanks for the visit, and for reading!

Sharon and the team.

Labels:

Cadet Bolam,

Cahir Healy,

Cathal O'Shannon,

Edward O'Carroll.,

Ellen Greer,

J H Thomas,

James Corr,

Roger McCorley,

Séamus Woods,

Thomas Johnson,

William Sibberson,

William Steele